The air hung heavy and still on the morning of Saturday, September 23, 1848, a stillness that felt less like peace and more like a held breath. The few hundred residents of the tiny village of Tampa and the soldiers stationed at Fort Brooke, surrounded by a largely unsettled Florida wilderness, had no modern warnings. The only signals were the phosphorescent glow that lit up the bay that night and an ominous, oppressive sultriness.

For some, an unease set in. Folks who had traveled into the post from the countryside cut their errands short, rushing home with a sense of foreboding. By Sunday, the winds began to gust, and the first showers started to fall. The tide, which would soon become a nightmare, was just beginning its treacherous rise.

The keeper’s gamble

At the mouth of Tampa Bay, on Egmont Key, stood the newly completed lighthouse. Its keeper, Sherrod Edwards, was a seasoned man of the sea, but nothing could have prepared him for what was coming. On Sunday morning, he watched the tide swell with alarming speed. Within minutes, two feet of saltwater surrounded his home. He had to think fast, with his family’s lives hanging in the balance.

Edwards loaded his family into his boat and, wading through the rising water, tied the vessel to the strongest palmetto trees he could find at the highest point of the tiny island. For hours, they swayed and bobbed in the violent winds, clinging to a boat tethered to trees. The next day, after the worst of the gale had passed, they found the boat—still intact, but lodged high in the treetops.

Tampa’s last stand

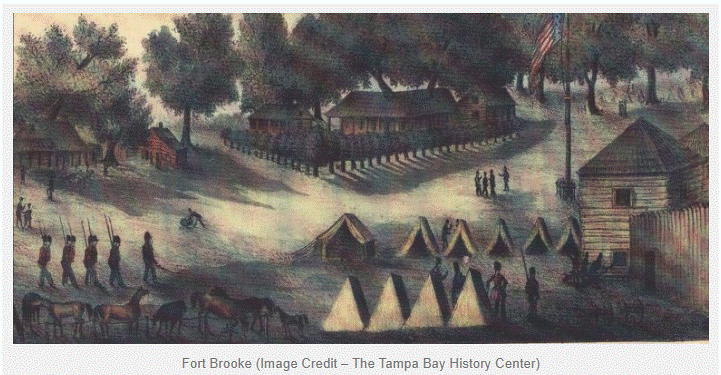

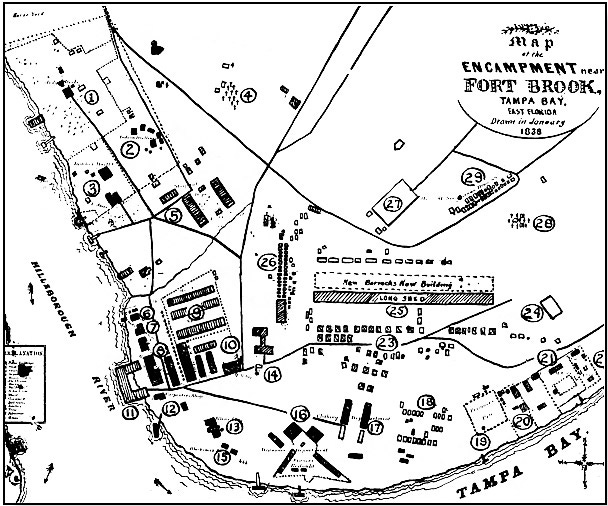

In the heart of the storm, as the winds screamed and the bay became a monstrous, churning beast, the residents of Fort Brooke faced annihilation. The barometer, a marvel of 19th-century technology, plunged to a terrifying 28.18 inches (954 mb). The military post’s surgeon later wrote that the water had risen an astonishing 15 feet above low tide.

Young Juliet Axtell, the chaplain’s wife, wrote in a letter that Tampa “was no more.” Her words were not an exaggeration. The storm surge swallowed Fort Brooke, battering and ultimately destroying the barracks, the church on the beach, and the Indian agent’s office. The garrison and its dependents had retreated to higher ground, but they were nearly submerged. One observer wrote that the only things visible were the very tops of the trees.

When the sun finally rose on Tuesday, September 26, the silence was as unnerving as the storm’s roar had been. In the town, only five buildings were left standing, and every one of them was damaged. Every ship in the port had been torn from its moorings and driven upriver, smashed to pieces.

A changed landscape

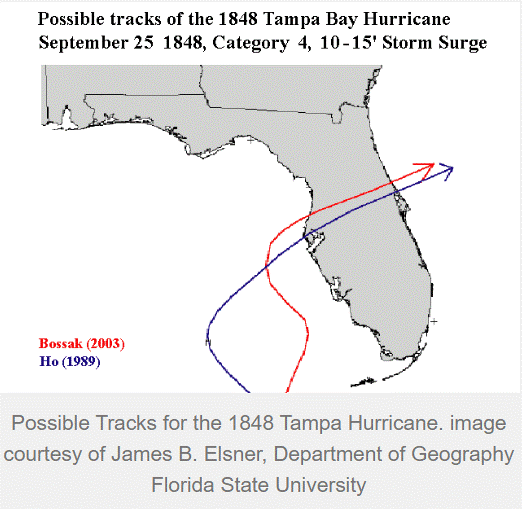

The Great Gale of 1848 didn’t just break man-made structures; it rewrote the map of Florida’s west coast.

- New Passages: The powerful surge tore through barrier islands, carving new inlets and channels where none had existed before. John’s Pass in Pinellas County and New Pass in Sarasota County were both created by the storm’s brute force.

- A Divided Peninsula: The storm surge was so immense in the Pinellas peninsula area that the Gulf of Mexico met Tampa Bay, effectively cutting the land in half.

- The Second Punch: Just a few weeks later, as the shell-shocked survivors were picking up the pieces, another hurricane struck in mid-October. Though not as strong as the first, it delivered a second blow, bringing a 10-foot storm surge and reminding Tampa just how vulnerable it was.

Today, the modern city of Tampa, with its high-rises and robust infrastructure, seems a world away from the vulnerable outpost of 1848. The story of the Great Gale is a stark and chilling reminder that the bay’s tranquil waters hold a terrifying power, a lesson etched into the very coastline by the “granddaddy of all hurricanes”.

About: Ocean Weather Services